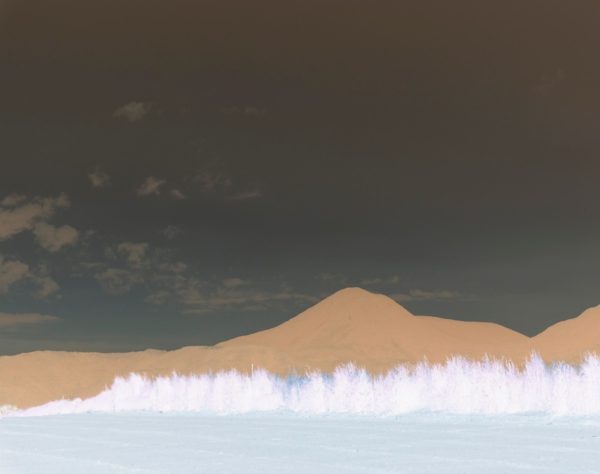

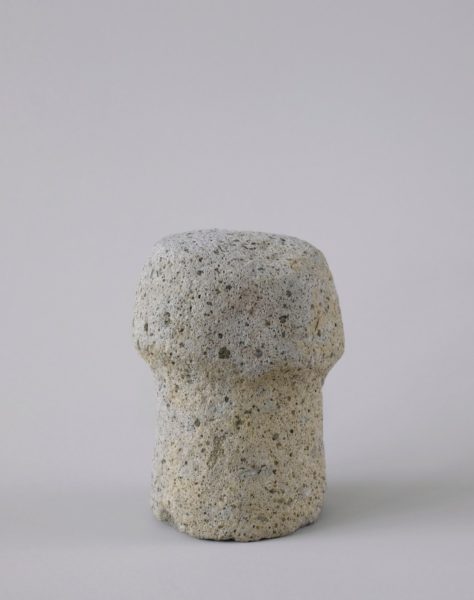

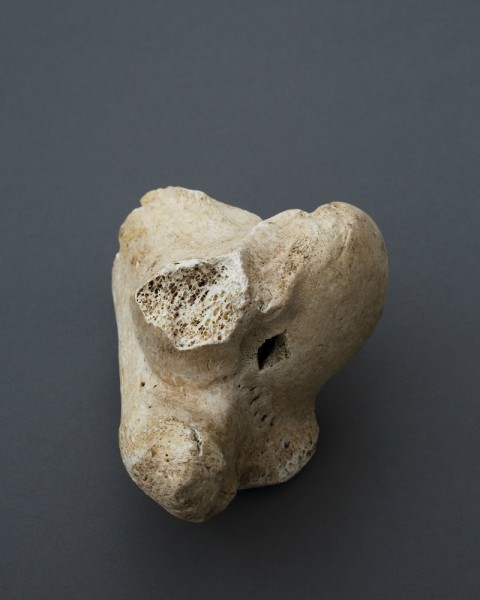

本展では、津田が9年前から日本の基層文化を見つめ直すため、始めたという縄文歩きの過程で出会った縄文時代の遺物や風景を撮影した「Grassland Tears(草むらの涙)」シリーズより、とくに八ヶ岳山麓、及び諏訪湖周縁を中心とした写真、約30点を展示します。津田は、数千年の時を経て、現代に受け継がれてきたこれらの遺物をモノとして捉えるのではなく「形ある霊魂」であり、「循環する命」そのものだと考えます。そして、写真という表現媒体を通じて、遺物を写し撮る際に、時としてその姿を紐解くべく像の階調を反転させた作品を制作することがあります。反転させた世界=ネガの世界のうちに、暗闇には光が灯り、光には暗闇が仕舞われているのだと語ります。 (「湖の目と山の皿」展@八ヶ岳美術館 展覧会チラシより抜粋)

In order to take a deeper look at Japanese fundamental culture, Tsuda started his Jomon exploration 9 years ago, and his “Grassland Tears” series is a collection of photographs of relics and scenery of the Jomon period. From the series, 30 photographs mainly taken at the foot of the Yatsugatake Mountains as well as at the edge of Lake Suwa are exhibited here. Tsuda feels that these relics handed down through generations for a few thousand years should not be treated as mere objects but as “spirits with a physical form,” in other words, symbolizing “reincarnated life.” When presenting those relics using photographs as media of representation, there are occasions when he results in producing works by inverting gradation of the objects in order to disclose their true meanings. In the ‘reversed world=world of the negative,’ it is indicated that there is light in darkness and darkness is hidden within light. (From a leaflet of Eyes of the Lake and Mother Mountain Plate exhibition at Yatsugatake Museum)

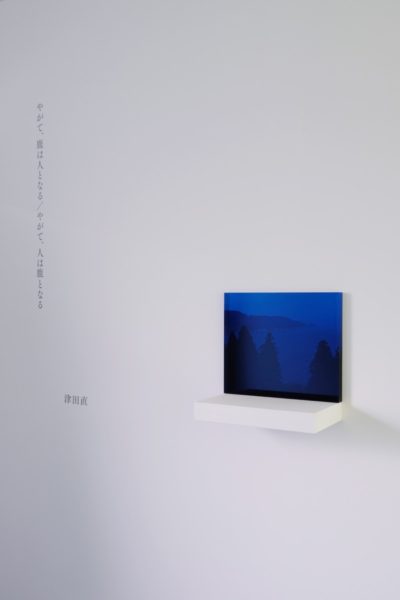

東北地方に三百年以上前から伝承されてきた鹿踊(ししおどり。獅子踊、鹿子躍などとも書かれる)。五月初旬、岩手県大船渡市と宮城県南三陸町にて現代まで受け継いできた保存会の方々を訪問し、家々を練り歩く鹿踊に同行、装束などを見せて頂いた。八人が扮した鹿たちは、時に勇壮に舞う姿も見せるが、一方で死霊を慰めるように静かに口伝を唱え、万物を供養するという役目を担う姿を目の当たりにした。

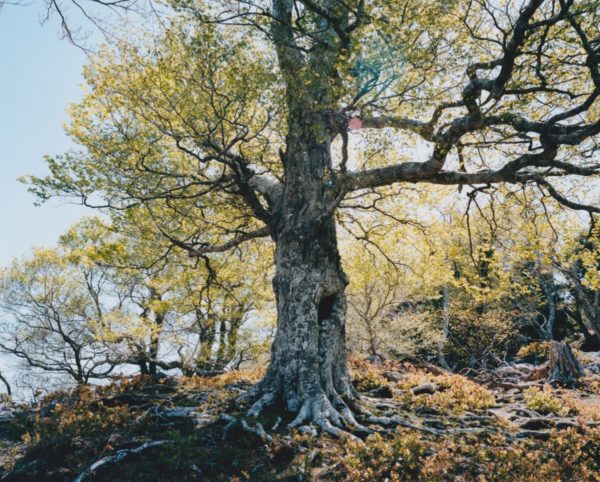

石巻に戻り、猟師とともに森の中を歩いた。先程まで牡鹿が居たと思われる斜面では、仄かに漂う気配を感じながら、微かな匂いを嗅いだ。鹿たちの獣道を教わるためだった。その道では、角で傷つけられた樹々に目が留まった。陽光が差し込み、樹がこちらを覗き込んでいる。僕は手に握っていた鹿角を、森へと差し出した。 (「やがて、鹿は人となる/やがて、人は鹿となる」、「Elnias Forest」展@Reborn-Art Festival 2019 会場テキストより抜粋)

For more than three hundred years, the folklore dance culture: “Shi-shi Odori (Deer Dance)” has been spread in variations and inherited over the wide region of Tohoku. Early in May, 2019, at Ofunato city in Iwate prefecture and Minami Sanriku town in Miyagi prefecture, I visited the members of several organizations who have cooperated to preserve those folk traditions to the present. They gave me opportunities to accompany with the parade of “Shi-shi Odori” to each of the individual houses in some local areas. Also they shared the knowledge with me on their characteristic costumes including ornaments and musical instruments etc. As a form of folk performing arts, eight players as deer demonstrate a brave and dynamic dance to the public. However, I was convinced that their another important role was to perform religious ceremony in the local community, when I observed their ritual form of prayer to recite calmly the traditional chant of requiem for ancestors and to hold a memorial service for all the spirits.

Later, in Ishinomaki city, I walked in the forest with a hunter. He introduced me to a slope where we supposed that a male deer must have been there for a moment ago. Sensing a hint of his presence around us, we smelled his scent in the air to follow him. Actually it lead us to the hidden trail of wild deer. On the way of tracing that track, marks on the surface of trees which deer carved with antlers attracted our notice as a sign. Eventually, I found a tree in the ray of sunlight casting a gaze towards me. To correspond to it, I presented an antler of deer in my hand to the forest, in return. (Text from Eventually, Deer Become Men / Eventually, Men Become Deer exhibition at Reborn-Art Festival 2019)

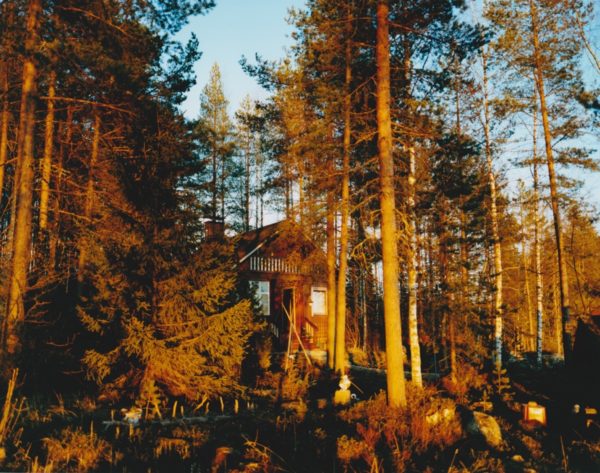

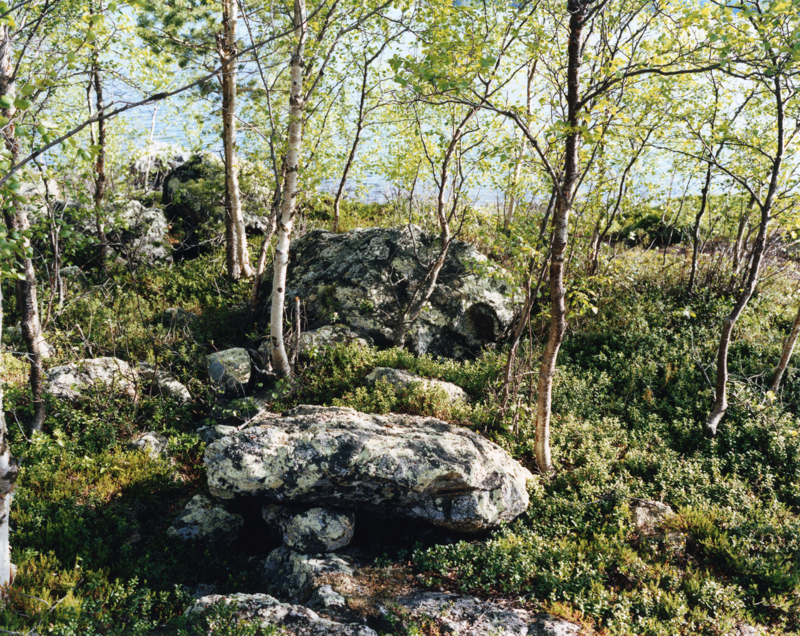

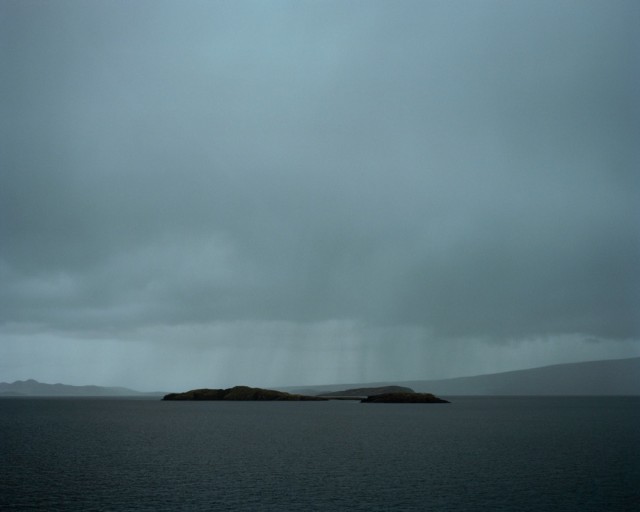

北欧に位置するフィンランドでは、夏の訪れが日本に比べて遅くにやってきます。初夏を迎えた5月、僕は南西部に在るヴァーノ島に滞在していました。フィンランドの沿岸地域にはおよそ40000もの島が在ると言われています。バルト海に面する近くの群島だけでも3000は在り、キミト島の先端にあるカスナスの港からフェリーでヴァーノ島へ向かう途中、僕は島影ばかりを眺めていました。友人に紹介された赤い屋根のコテージに辿り着き、島を歩き始めると、数日前まで固く閉じていたであろう新芽が、開こうとしているのが目に留まりました。眩しい陽光が数日照らし続けたことで、一気に夏がやってきたのです。岩陰から伸びゆく草木。新緑に萌える木の葉は、まだ雛鳥の産毛のように柔らかく、風に揺れていました。普段は人口15人程の小さな島で、空を飛ぶ白鳥の羽音までも聞き取れるくらい静かです。けれど、夏の間は繁殖のために渡り鳥が集まり、羽根を休めるように、フィンランドの人々も休暇を過ごすために島を訪れるので、賑やかな季節がやってきます。この旅で出会った人に島への道を尋ねたところ、彼はヘルシンキから船でやって来たといいます。ここへやってくる人々にとって夏の休暇は、それぞれの船旅と共にあるようです。 (「辺つ方(へつべ)の休息」展@太宰府天満宮 会場テキスト「群島での夏のはじまり」より抜粋)

In Finland, situated in Northern Europe, the arrival of summer is much later than that of Japan. In the early summer month of May, I was staying at Vänö Island, in southwestern corner of Finland. 40,000 islands are said to exist in the coastal area of Finland. Archipelago facing the Baltic Sea is said to number 3,000, and while heading to Vänö Island in a ferry from Kasnäs harbor at the tip of Kemiönsaari, I was constantly following vague outlines of islands in distance. After reaching the red roof cottage recommended by my friend and setting out for a walk, numbers of new buds which were probably not seen until a few days before caught my eye. They were just about to sprout. The bright sun shining for a few days called for the summer all at once. Plants were beginning to grow from rock crevices. Fresh green leaves of trees, appearing to be soft as peach fuzz of baby birds, were swaying in the wind. Its regular population being only 15, the tiny island was so quiet that we were able to hear flapping of wings of swans flying above. But, during the summer months, the island becomes lively with visitors coming on vacations as though migrating birds resting their wings when they gather for breeding purposes. When I asked a traveler whom I met during my stay how he came to the island, he told me that he came from Helsinki by boat. It seems that summer vacation for those who come to the island is always together with each person’s boat trip. (Text from Beginning of Summer in an Archipelago by Nao Tsuda, Tranquility at the Shore exhibition at Dazaifutenmangu)

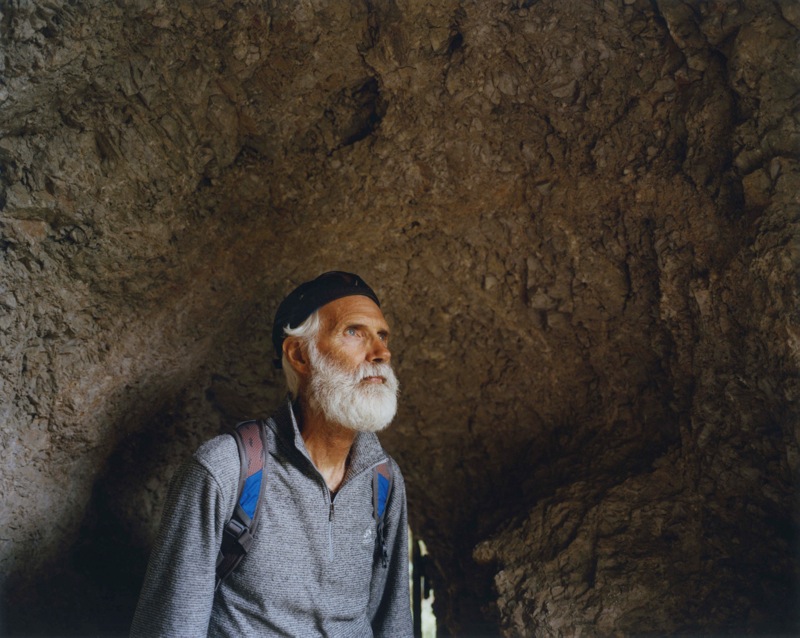

ここは森の入口。ここから、どう歩くのか、どこへ向かうのかは自由である。小さな森のようにも、深い森のようにも思える。森とは、明確な形のない、往々にしてとらえにくいものなのだ。

津田直もまた、森の入口に立った。5年前、リトアニアを訪れた時のことである。日本から約8000km離れたこの小国は、私たちの多くにとって未知の場所だろう。意外なことに同じヨーロッパでも、リトアニアを遠い存在だと感じる人は少なくない。それは、地理的な要因に加え、近隣大国による侵略が続き、28年前まではロシアの占領下に置かれていたという歴史的背景、そして、遡ればリトアニアがヨーロッパで最後にキリスト教を受け入れた、いわば異端の地であったこととも無関係ではない。この地域には、元々は日本と同様に多神教信仰が根づいており、太陽、星、雷や動植物などの自然を崇拝するアニミズムが浸透していた。

津田は、これまでも異端の地を旅してきた。しかし、それは異端であることが理由だった訳ではなく、「消えゆくものを、写真を通してつなぎ止める」という揺るぎない姿勢を貫くとき、モロッコやモンゴルの山峡、北極圏、ヒマラヤ、ミャンマー、沖縄などの奥地にたどり着いたのは必然だった。津田を呼び寄せた、消えゆく「もの」とは何であろう。それは、「文化」という言葉に近いかもしれないが、一語では到底括りきれるものではない。それは、言語化すればこぼれ落ちてしまう「何か」、決定的瞬間をとらえた1枚だけでは語れない「何か」である。津田はこうした形を持たない「何か」を、口承のように、余白や間(はざま)、象徴を織り交ぜながら記録する。口承に用いられる言語は場所や時代が変われば理解は難しいかもしれないが、写真という視覚言語は時空を超えるだろう。津田の写真は、時と、場所と、私たちがすべて一本の線で結ばれていることを静かに告げている。

ここにある作品は、その森が、遠くの小さな国に、すぐ近くに、古代に、現代にも未だあることを、そして、この先も存在し続ける希望を示す。来た道を戻ってもよい。気に入った場所で佇んでもよい。こうした体験を通して、私たちと森はより強くつながっていくのだから。 (「エリナスの森」展@三菱地所アルティアム 序文 菊田樹子)

Here the entrance to a forest is open. Then it’s your own choice how to walk through it and to which direction to take a step. It might appear to be either a small and deep forest. As general the entity of a forest is something obscure to specify the outline and often hard to figure out.

It was five years ago that Nao Tsuda also arrived at a door to a forest when he visited Lithuania for the first time. For most of Japanese people, such a small country about eight thousands kilometers away from Japan might be a strange place. However, to our surprise, it is parallel even to many people in Europe that Lithuania is regarded as somehow unfamiliar nation state. In addition to the geographical factor, its historical background can bring such a sense of distance from other nations. Following a period of invasion by neighboring powers, it had been under the rule of the former Soviet Union until they won the independence twenty eight years ago. Moreover, considering a long religious context, it matters the fact that Lithuania had been recognized as the land of “paganism” and it was the very last pagan state that adopted the conversion to Christianity among all the European nations. Originally in this region, the ancient religious framework of polytheism had been deeply rooted, which we can find a similarity to that in Japanese and the animism in worship for the nature, including the sun, the moon, stars, the thunder and creatures of both plants and animals had been predominant throughly among their folk.

As a photographer, Nao Tsuda has traveled around various distant lands across the world. Actually his journey was not motivated by the heretical context in the locations, but indeed he constantly pursued his original way based on a firm faith in his mission: “To tie up with something that is going to disappear in the world thorough the art of photography”. As a natural consequence, he found himself inevitably oriented to those hinterlands or the deep interior of characteristic fields such as valley and mountains in Morocco or Mongolia, the Arctic regions, Himalaya, Myanmar and Okinawa Islands etc. What is “something that is going to disappear” that lead him to work for it? One can never define and comprehend it at all in a single term such as “culture” even though it seems to approximately represent it. We have to compromise that “something” is what any trial of verbalization ends up in losing its essence and a piece of fragmental picture that shot a decisive moment can’t describe completely. To record “something” like that which is impossible to deal with any form, Nao Tsuda composes a tapestry, editing symbolic elements with marginal or interval space, as if making an archive of oral history. To hand over memories in the oral tradition, it happens that the language itself would make it difficult to understand depending on conditions of times and locations. On the contrary the visual language of photography is universal to transmit the contents beyond the realm of time and space. Then we can perceive his works of photography silently affirm a status that time and space and our being are all tied together in a line.

This exhibition of a series of works shows us not only the situations that this forest actually exists in a small distant country but also it does just close to ourselves to relate ancient and modern times and further, it manifests a hope of the possibility that it will continue in the future, too. To appreciate the entity of Elnias Forest we can go back our way at any point, or can find some spot to stay and stand still where we want. All those processes are essential to our experiences that enable us to come to connect with the forest more intensively. (Text of Elnias Forest exhibition at Mitsubishi Estate ARTIUM, Preface by Mikiko Kikuta)

沖縄という土地との出会いによって、僕は日本という国の多様な文化的背景を幾度となく更新させてきたか分からない。自然と人間との距離の近さや土着の宗教観…死生観に至るまで、その在り方は本土とはかなり異なる世界が展開していて、特に自然を崇める人々の慎ましい行いや民間信仰として祖先崇拝が今日まで息づいていることは、文化として奥深いとしか言いようがない。それを端的に象徴していることのひとつとして、沖縄の多くの家には今日でも新暦(太陽暦)に加えて、旧暦(太陰太陽暦)の載ったカレンダーが掛かっている。それは、沖縄が四方を海に囲まれた島であり、台風や猛暑などの厳しい気象条件の中で漁撈や農耕を行う為、潮の干満や種蒔き、収穫のタイミングを図ることのできる旧暦が用いられてきたということでも十分納得ができるが、海の生活や農家の暮らしを通じて、季節の節目に祭事や行事が行われていると聞いて、さらに頷けるものがあった。

(中略)

伊平屋島に隣り合う伊是名島では、伊是名集落で唯一の神人である森茂さんというおじぃから、島の神事について度々教わっているが、そこでもすでに伝統を継承していくことは、集落の次世代の人々にとって課題となっている。しかし、僕のような外からやって来た者が、どうこういう話ではそもそもない。だが、だからといって古から受け継がれてきた祭事の存続が危ぶまれ、消滅していくのかと言えば、僕にはそうは思えない。なぜなら、島々を歩き回った日に出会った人々や、清明祭(方言でシーミーと言い、新暦の四月五日頃の清明入りから二週間の間に行われる先祖供養の行事)やお盆などの行事を共に過ごさせてもらった家族のそばにいると、祈りとは目に見えて映る光景ばかりではないということが、うっすらと分かってくるようになっていったからだ。以前の僕ならば、祈りとはその姿勢を指す言葉であると思っていた。しかし今、僕が感じ取っている祈りとは、人々の内側から湧き上がった本能的な唱えが祈りの声や神歌となり、音となって現れるようなものであって、様相や形式、振りといったものは、後々になって調えられたのではないかと思っている。言うならば、祈りの源泉はもっと深淵なる場所に在り、その境地に至った者たちは、自らの内に泉を見出し、人々は生涯を懸けてその泉を枯らすまいと、祈りを日々捧げてきたのではないかと思えてくるのだ。沖縄に見られる御嶽などの聖地には、本土の宗教のような立派な社や祭壇が見られず、教典がないのは、そうした所以ではないだろうか。 (『IHEYA・IZENA』津田直テキストより)

Having encountered with land called Okinawa, I do not know how many times I had renewed the various cultural background of Japan. Proximity of distance between nature and mankind, indigenous religious views extending to views of life and death; reality reveals a great deal of difference from those of mainland Japan. Humble behavior of those respecting nature and ancestor worship, still holding an important part in their present life, strongly supported the depth of their culture. As one aspect of its straight forward symbolism, many households in Okinawa still use the old lunar calendar along with solar calendar. We can fully understand and accept the fact that in Okinawa, an island surrounded on all sides by sea, severe weather conditions such as typhoons and intense heat wave greatly affected their fishing and farming, and the old lunar calendar was always very useful in checking the rise and fall of the tide as well as in planning adequate timing for planting and harvesting. Furthermore, I was very much convinced to know that many of the sacred rites and traditional events related to their daily lives of fishing and farming took place at the turn of their seasons.

(Omission)

At Izena Island, which is an island next to Iheya Island, gramps Morishige-san, who happens to be the only remaining kaminchu in Izena community, has taught me about various rituals of the island, but he has also mentioned that one of the big themes for next generation community people is the succeeding of traditions. However, someone like myself, who is completely an outsider, is in no position to make a comment on the matter. Yet, I am not fully convinced that there is a fear that these rituals handed down for generations are unlikely to continue and will become extinct. It is because, through being in contact with people whom I met on the day I walked around the island and whom I spent time together participating in each of the rituals with a family at Seimei-Festival (called seeme in the area as an Okinawan dialect, pertaining to ancestor worship at graves taking place within two weeks after Seimei, one of thetwenty-four divisions of four seasons, which comes around April 5th on solar calendar) and Bon Festival, welcoming deceased ancestors in each family household, I have come to vaguely feel that praying was not only what we saw in the action of the people. In the past, I probably would have interpreted prayers to be words explaining people’s actions. However, what I feel to be a prayer now is something that has swelled up from the bottom of one’s heart as an instinctive chant, becoming voices of prayers and songs for gods. I believe that it appears as sounds, with looks, formats, and actions added on later. In other words, I feel that the origin of prayers exists in the depth of someone’s heart, and those that have reached the high spiritual ground are able to notice one’s own spring within themselves. With such accomplishment, they will continue to devote their lives to avoid the spring from drying up and will continue to offer daily prayers. Such is the reason, I believe, for the sacred places such as Utaki in Okinawa not having gorgeous shrines and altars and not possessing any scriptures as in other Japanese mainland religions. (From IHEYA・IZENA, Text by Nao Tsuda)

津田の「縄文歩き」はその土地に今でも残る縄文時代の生活の痕跡を身体で解いていく作業であり、それらの集積は研究者的な視点による事実の体系化に留まることなく、作家の関心は自然観・死生観・時の捉え方など、縄文時代の精神文化へ向けられています。

これらの縄文・続縄文時代の遺物は、単なる「モノ」ではなく、「形ある霊魂」であり「循環する命」そのものなのだと津田は考えます。その姿を紐解くべく像の階調を反転させた作品について、作家は、反転した世界=ネガの世界のうちに、暗闇には光が灯り、光には暗闇が仕舞われているのだと語っています。

生きとし生けるものは、この世に姿を現すときよりも、姿を消してゆくときの方が、よりその存在が露わになるのではないだろうか。一万年という果てしない地層を一頁ずつめくり、闇と影の間に光が蘇ったとき、我々の目には何が映り、何が残されてゆくのだろう。(Taka Ishii Gallery「Grassland Tears」展プレスリリースより)

Through his “Jomon walks”, Tsuda also physically experiences the traces of Jomon era life that remain in the local regions. Going beyond the researcher’s objectification of accumulated data, Tsuda has directed his attention to the spiritual culture of the Jomon period and its perspectives on nature, time, and life and death.

For Tsuda, these Jomon relics are not mere objects. They are instead “spirits with physical form” and “reincarnated life”. Regarding the images of these objects, which he has produced in negative to disclose their true meaning, he explains that in the world of the negative, i.e. the reversed world, there is light in darkness and darkness hidden within light.

All living things disclose their existence more fully in their disappearance from than their appearance in this world. When we turn the pages of a seemingly eternal, ten thousand years of geological layers, one by one, and light returns to the space of darkness and shadow, something is reflected and retained in our eyes.(From the press release of “Grassland” Tears exhibition at Taka Ishii Gallery)

先に津田の旅を人類学者のフィールド・ワークになぞらえた。だがそれが決定的に違っているのは、彼が人類学者のように、未開の人々の社会・言語・文化などを調査・研究することで、人類の思考や行動を論理的、体系的に構造づけようなどとは毛頭考えていないことだ。彼が写真撮影によって成し遂げようとしているのは、むしろ「静けさ」、「白さ」、「遠さ」といった独特の「しるし」を持つ人たち=Mentorたちにとっての世界像を、写真というこれまた独特の視力を備えた装置によって、ありありと浮かび上がらせるということに他ならないのではないか。(『NAGA』飯沢耕太郎テキストより)

Earlier, I compared Tsuda’s trips to an anthropologist’s fieldwork. What is definitely different is the fact that Tsuda has no will to form logical and systematic structure of human thinking and behavior by investigating these desolate places and people by their societies, languages, and culture like an anthropologist. Instead, what he is trying to achieve in photography is to bring into surface, using a unique equipment called photography, the perspectives of those Mentors who possess unique marks such as “silence,” “whiteness,” and “distance.” (From Naga, Text by Kotaro Iizawa)

写真はフィリピン・ルソン島のピナトゥポ火山周域のものだ。ピナトゥボ火山は、90年代初頭に大噴火したが、その成層圏にまで達するほどの噴煙と灰により、その年、世界中の夕焼けが異様なまでに赤く変化したほどだった。大地は吹飛ばされ火口湖となり、大量の灰が地につもり、土石流を生み、土の河が人も家も森林すべてを洗い流した。まるでノアが体験した洪水のようだ。破壊に見えてしかし、それは、「新しい道」の出現でもあった。その地に住む者(彼らは2万年前からピナトゥボ山麓に住みつき、肌の色が黒いのでネグリートと呼ばれる)は、荒涼たる場所から、新しくくらしを生む。津田はその中のアエタ族の集落で一時を過ごす。その首(おさ)であるローマン・キングととも行動し、さまざまなことを教わることになる。灰の中から最初に芽を出し、実るのは、amukawとよばれるワイルドバナナであった。子どもたちが、磁石を使って河原の水の中から砂鉄をとって売る。ここには、近代文明がつくったものなどは、一切流されて、無い。ある日津田が、ローマン・キングに誘われ山の頂上で見たものは、かなたから来る人々の姿だった。彼らこそ、大噴火後も先祖から受け継ぐピナトゥボの神、アポ・ナマリアーリを信仰するため、再び山のそばへ帰っていった人々だ。 灰混じりの川を数時間かけて歩き集う者たちは、互いの物を交換しあい、くらしに必要な糧を得る。火山の破壊のあとで生まれたもの、景色の中で交わり生まれるもの。小さなワイルドバナナは糧の中心的存在であり、心である。津田は、それを知る。 (「On the Mountain Path」展@Gallery 916 後藤繁雄 「山の目になる 津田直の写真のために」会場テキストより抜粋)

Photographs are of the area around Mount Pinatubo on the island of Luzon in the Philippines. Mount Pinatubo experienced a major eruption in the early 1990s, billowing smoke and ash as far as the stratosphere to the extent that in the year in question sunsets around the world turned unusually red. Earth was thrown into the air and a crater lake was formed, a large quantity of ash accumulated on the ground, and lahars occurred, sweeping away people and houses and forests in rivers of mud. It was almost like the flood that Noah experienced. It looked like complete destruction, but at the same time it represented the appearance of a “new path.” The people living in the affected area (who settled at the foot of Mount Pinatubo more than 20,000 years ago and are referred to as “Negrito” due to their dark skin color) are forging new lives out of this scene of destruction. Amidst this, Tsuda spends time in an Aeta village. He works alongside the village headman, Roman King, and learns various things from him. The first plant to put its head above the ashes and produce fruit was a wild banana known as amukaw. Children use magnets to remove iron sand from the riverbeds, which they then sell. Here, everything produced by modern civilization is gone, washed away by the lahars. One day, Tsuda is led by Roman King to the top of a mountain from where he sees people approaching from the distance. They are people returning to live by Mount Pinatubo, drawn by their faith in the deity of the mountain, Apo Namalyari, a faith that remains strong even after the 1991 eruption. Gathering after walking for hours along rivers clogged with ash, they exchange belongings and acquire enough provisions to make a living. New customs that emerged in the wake of the destruction wreaked by the volcano, changes in the surrounding landscape. The small wild bananas play a central role in providing nourishment, both physically and spiritually. This much Tsuda knows. (From the text Becoming the eyes of the mountains – Looking at Nao Tsuda’s photographs by Shigeo Goto, On the Mountain Path exhibition at Gallery 916)

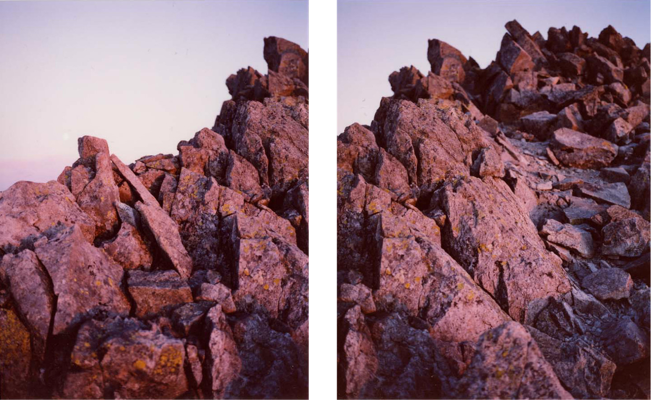

2013年夏、アーティスト・イン・レジデンスプログラムでスイスのクラン・モンタナにて滞在制作した作品。

2013年9月に訪れたスイス・ヴァレー地方の滞在制作では、はじめにその土地を歩き回ることからフィールドワークが始まった。僕は標高4000m峰が連なるアルプスの山脈に囲まれた地域で、谷から谷へと渡り歩き過ごした。それはまるで天から降り注いだ雨水が自ら川を築き、山に線を描いてゆくような流れと近いものだった。

その過程でいつしかBisse(ビス)と呼ばれている水路、さらにそこへ寄り添う細い山道と出会い、その魅力に僕は引き込まれていった。Bisseとは氷河から溶け出した水や雪解け水を活用した灌漑用水路の名称で、千年近く前から村人が中心となり建設・管理してきた。かつては、主に牧草地に水を運び動物たちや農地を豊かにするためのものであったようだが、今では葡萄畑に引かれたものなどが一部その姿を留めている。

ヴァレー地方独特である山間部の水路は、途切れ途切れではあるが今でも各所に残されていて、地図から探り出しては繋ぐように歩いて回った。すると足音は水の流れに掻き消され、身体は水に運ばれてゆくような錯覚を起こし、ぐっと山に近づいた気持ちとなっていった。

又、Bisse du Ro やBisse de Vercorinでは伝統的な工法で水路を修復する男達とも出会うことができた。Bisseを流れる水は水源に始まり、山の傾斜を活用した水路を経て、やがては人々の暮らす土地を目指してゆく。だが途中には絶壁もあり、そこでは木で組まれた箱型の水路が水を溢さぬように運んでゆく。 (「Crossing Views I」展覧会カタログ、津田直「NOAH」テキストより)

A series which has made by artist in residence at Crans–Montana in Switzerland on Summer, 2013.

In September 2013, I went to the Valais region of Switzerland to do an artist residency and began my fieldwork by going about on foot. I spent the days walking from one valley to another, surrounded by a continuous range of Alpine peaks soaring to an altitude of 4,000 meters. These journeys, I felt were almost like rivers formed of fallen rain, etching lines in the mountains.

At one point during my preambulations, I came across and became enchanted by ancient water channels and the narrow mountain trails that led to them. Fed by snowmelt or glacial runoff, these channels, called “bisse” in French, have been built and maintained for almost a thousand years largely by villagers as a source of irrigation water. Thanks to the bisses, which were constructed mainly to water the pastures, livestock and farmland flourished. Only some of these channels, like those used to irrigate vineyards, still exist in their former condition.

The bisses are a distinctive feature of the mountainous areas within Valais, and though largely discontinuous, can still be found in various places. I located them on the map and visited each one on foot, as if I were connecting them. During my approach, the sound of my footsteps would be drowned out by the sound of water, giving rise to the illusion of being carried by the flow, of being closer to the mountains.

Following the Bisse du Ro and Bisse de Vercorin, I encountered men who use traditional techniques to repair and maintain these water channels. Starting from their source, the bisses carry water down the mountain slopes to locations inhabited by people. To prevent the water from falling off the face of cliffs along the way, box-shaped channels made of wood were constructed to carry the flow. (From Crossing Views I exhibition catalog, “NOAH” text by Nao Tsuda)

僕はこれまでにも各地でのフィールドワークにおいて、自然と人間が向き合い対話するという場面に幾度となく遭遇してきた。この旅の始まりにもそんな予感がすでに働き、僕は引き寄せられるようにサーメ人の土地=サーメランドに辿り着いたのだった。 (『SAMELAND』津田直テキストより)

現代日本という社会を共同で営んでいるわれわれの中で、おそらくもっとも遠い旅人のひとりである津田直の旅は、一貫して辺境をめざしているようだ。辺境、すなわち、都市機能から遠いところ。中でも首都の、みずからを中心化する作用から、可能なかぎり離れたところ。端的にいって人が少ないところ。そして少ないがゆえに逆説的にも、人類史の真の伝統がよりよく守られているところ。いったいいくつの土地の話を、ぼくは彼から聞いたことだろう。 (『SAMELAND』管啓次郎テキストより)

In the fieldwork I had previously conducted around the world, I often stumbled upon people who live among nature and attempt to earnestly communicate with their surroundings. With a slight premonition of such an encounter, I arrived in Lapland, also known as Sameland, where many Sami people live. (From SAMELAND, text by Nao Tsuda)

Nao Tsuda, without any doubt one of the ‘furthest’ travelers among us who share contemporary Japanese society in common, constantly travels to the fringes of the globalized world. By the fringes I mean the places far from the efficiency and functions of the urban space, especially the places as remote as possible from the self-centering workings of the capital. Simply put, he goes to places where few people live. The fewness of number, paradoxical as it may seem, protects humanity’s central traditions. How many such place names have he mentioned to me so far? (From SAMELAND, text by Keijiro Suga)

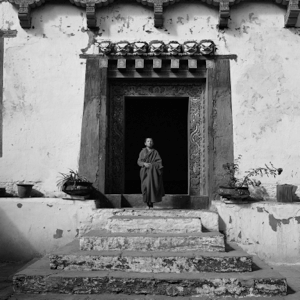

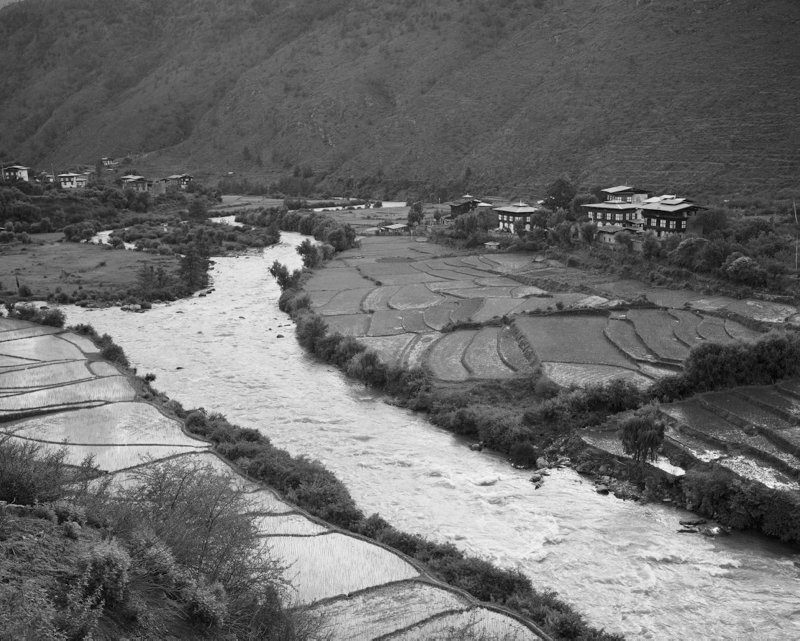

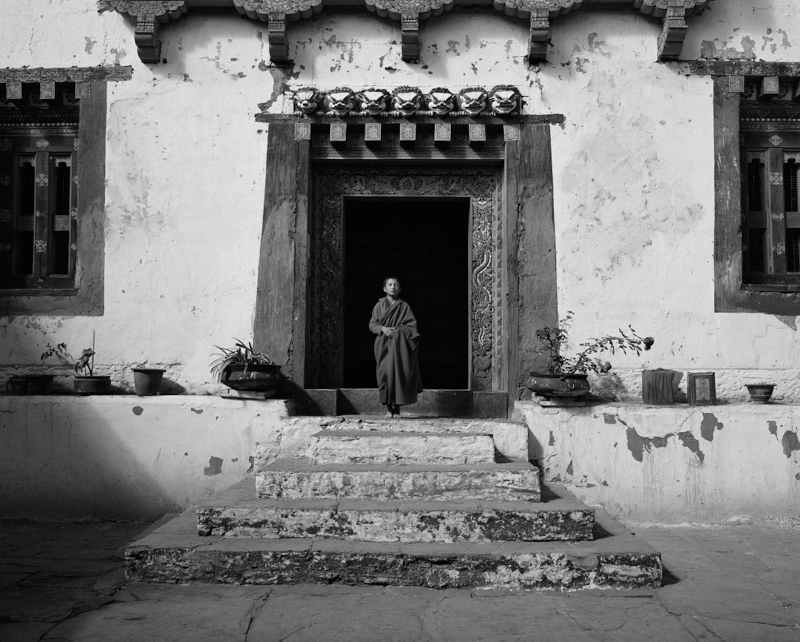

ブータン王国はチベット仏教を国教としているヒマラヤ山麓に佇む小国。

その大きさは九州くらいだと喩えられることがあるが、思いの他 その土地は広く感じられる。神仏のみならず自然界に対しても敬意を表するゆえに、山へトンネルを掘るようなことをすることなく、いまなお人々は地形に沿って往来する日々を送っている。だからブータンでは時間が緩やかに流れ、谷間のように深い信仰を今に受け継ぐことができたのだろう。

四度に渡り旅をしたブータンでは、国際空港のあるパロの町を玄関口に、首都であるティンプー近隣の寺院を巡り、北部へと連なる山道では、遊牧民と共に聖山を拝みながら歩んだ。さらに東へ向かい古刹の点在する中央ブータン・ブムタン地方を訪ねた。四季を通じて催されるツェチュ祭では、僧侶を中心とした仮面舞踊が繰り広げられ、人々の篤き信仰心に触れた。 (「REBORN (Scene 2) -Platinum Print Series」展@Taka Ishii Gallery Photography / Film プレスリリースより、津田直テキスト)

The kingdom of Bhutan is a small Tibetan Tantric Buddhist nation standing at the foot of the Himalaya Mountains. It is said that Bhutan is comparable to Kyushu in size, but it feels surprisingly larger. As its people revere not only deities and Buddhas but also the natural world, the production of such an invasive structure as a mountain tunnel is out of the question. In Bhutan, people continue to travel according to the natural topography. Time, therefore, passes gently in Bhutan; Tibetan Tantric Buddhist beliefs, deep as ravines, can be passed down through the generations here. I traveled to Bhutan four times. I arrived each time in Paro, where the international airport is located, and visited the temples in Thimphu. I then traveled on mountain trails leading north and worshipped holy mountains with nomadic peoples. I also traveled to the Bumthang district to visit its many ancient temples. During the Tshechu festivals, held in all four seasons, monks performed masked dances. I was moved by the devotion of the Bhutanese people. (From the press release of Taka Ishii Gallery Photography / Film “REBORN (Scene 2) -Platinum Print Series”, text by Nao Tsuda)

2010年より始まった「REBORN」シリーズは、世界で唯一チベット仏教を国教として守り伝えるブータン王国を撮影地としています。古くから神仏や自然界への畏敬の念が培われ、宗教が人々の生活に深く根差すこの地で、津田は仏教の原点や信仰の在り方について探求し続けてきました。チベット仏教で 信じられている輪廻転生を意味する「REBORN」と名づけられた本シリーズには、ブータン各地に点在する数々の寺院や僧院、その内奥に暮らす僧侶たち、繰り広げられる宗教的な祭りなど、ヒマラヤの厳しい自然に寄り添うように何世紀にも渡り守られてきた信仰と伝統の姿が写し取られています。 (「REBORN (Scene 2) -Platinum Print Series」展@Taka Ishii Gallery Photography / Film プレリリリースより)

The “REBORN” series, which Tsuda began in 2010, is shot in Bhutan, the only Tibetan Tantric Buddhist nation in the world. Tsuda has explored the origin and contemporary practice of Buddhism in Bhutan, a place where religion is deeply rooted in people’s lives and there is a tradition of reverence for deities, Buddhas and the natural world. This series takes its title from the Tibetan Tantric Buddhist belief in reincarnation, and the images here document the practice and tradition of this religion, which has been practiced over centuries in Bhutan in close proximity to the harsh natural conditions of the Himalayas. Tsuda has captured Bhutan’s many temples and monasteries, along with their monks and the religious festivals and rituals that are practiced inside them.

(From the press release of the exhibition “REBORN (Scene 2) -Platinum Print Series” at Taka Ishii Gallery Photography / Film)

東北地方は日本列島の最大の島、本州の北東部を占める地域で、青森県、岩手県、秋田県、宮城県、福島県の6県からなる。気候的にはやや寒冷だが、 海、山、川、森など美しく豊かな風土に恵まれている。日本に古代人が定住し始めた約15000〜3000年前の縄文時代には、独特の縄目模様の土器で知られる縄文文化がこの地域を舞台に花開いた。だが、西方の奈良や京都に政治や文化の中心が移ると、東北は遅れた未開発の地域として中央政権の支配下に置かれる。それでもこの辺境の地には、縄文文化の伝統を受け継ぐ生命力あふれる精神文化がずっと保ち続けられてきた。

その東北地方を中心に、 2011年3月11日にマグニチュード9.0という大地震が襲った。死者・行方不明者あわせて2万人に迫るという大きな被害を出したこの大震災と、直後の福島第一原子力発電所の危機的な事故については、多くのメディアで報道され、東北の県や都市の名前も耳に馴染んだものになった。だが、東北の気候・風土・ 歴史、そしてそこで人々がどんな暮らしをしているかについては、ほとんど知られていないのではないかと思う。

本展はその東北を撮影した 10人(9人+1組)の写真によって構成される。1950〜60年代の農村を撮影した千葉禎介、小島一郎、東北各地の民俗儀礼や祭りなどを追った芳賀日出男、内藤正敏、田附勝、自らの個人史と故郷の光景を重ね合わせる大島洋、畠山直哉、東北の美しい自然にカメラを向ける林明輝、縄文時代の遺跡を通じて日本人の精神の起源を探る津田直の作品、そして伊藤トオルをリーダーに、宮城県仙台市の「無名の風景」を集団で撮影した「仙台コレクション」のシリーズである。 (国際交流基金 巡回写真展「東北—風土・人・くらし」案内状、飯沢耕太郎テキストより)

Tohoku is the northeastern section of Honshu, the largest island in the Japanese Archipelago, and is divided into six prefectures: Aomori, Iwate, Akita, Yamagata, Miyagi, and Fukushima. Although it has a rather cold climate, it is blessed with a beautiful and bountiful natural environment of seas, mountains, rivers, and forests. Is is also known as a center of the Jomon culture, which was developed by some of the first people living in Japan. Known for the flame-like forms of its pottery, this culture flourished in Tohoku between 15000 and 3000 years ago. When the center of political power and culture shifted to Nara and Kyoto in western Japan, Tohoku was placed under the rule of the central government and regarded as a backward and primitive region, but this magical area maintained a vital spiritual culture that preserved the Jomon sprit.

On March 11, 2011 an earthquake of magnitude 9.0 struck Japan, and the worst damage was concentrated in the Tohoku region. The impact was devastating. It left 20,000 people dead or missing and caused the unprecedented unclear accident at No.1 Fukushima Nuclear Power Plant. The media coverage of the destruction made many people familiar with the names of Tohoku cities and prefectures, but few are likely to have a broad knowledge of other aspects of the region – its climate, natural and cultural environment, history, way of life, or people.

This exhibition is composed of photographers’ of the Tohoku taken by nine individual photographers and one photographers group. Teisuke Chiba and Ichiro Kojima photographed Tohoku in the 1950s and 1960s. Hideo Haga, Masatoshi Naito, and Masaru Tatsuki have recorded festivals and folk religious rites throughout the region. Hiroshi Oshima and Naoya Hatakeyama have combined their personal histories with the landscapes of their home regions. Meiki Lin turned his camera toward the beautiful natural environment. Nao Tsuda searched for the source of the Japanese spirit in relics and artifacts of the Jomon period. A group of photographers led by Toru Ito have created the Sendai Collection, a series of photographs of anonymous scenes in Sendai, Miyagi prefecture. (From the invitation of the exhibition “TOHOKU Though the Eyes of Japanese Photographers” by Japan Foundation, text by Kotaro Iizawa)

嵐が去った後 偶然発見された古代の住居跡が在ると聞き向かった

途中ストーンサークルを横断する時 真ん中に立ち 声を放つと

空気が膨らみ 波紋のように響き渡り 思わず後ろを振り返った

果てなき時間と戯れても 辿り着ける場所ではなかった

雨が降りはじめ 屋根のない家に飛び込んだ

水が土に染み込む音だけが道標となり 身体は運ばれてゆくようだった

組石の窓のそとに今は白い海が見える

来た道はもう遠くの線でしかなかった

足元の渦巻模様が階段の螺旋と重なり 円環は光の塔になっていった

(制作ノートより)

After a storm, I headed for the remains of ancient dwellings which were said to have been discovered accidentally.

On the way, while crossing the stone circle, I stood at the center and raised my voice.

The air seemed to have expanded, echoing like spreading ripples, and I could not help looking back.

No matter how long I spent my time, it was impossible for me to reach my destination.

It had started to rain, and I jumped into a roof-less dwelling.

I could only hear the sound of water soaking into the ground, and I felt as though my body was being washed away.

Now, I can see the white sea outside the stone assembled windows.

The path I took was already nothing more than a far distant line.

Whirling patterns at my feet, overlapped with spiral staircases, and the stone circle had become a shining tower.

(From a production note)

海鳴りが納まるころ、嵐は去っていった。

僕は自らの心音に安堵し、泥炭の炎に身体を暖めた。

すでに雨は上がり、海は凪ぎはじめている。

過ぎ去った時間の永さは分からない。

覚えていることと言えば、地面に渦巻き模様が幾つも刻まれ残ったことだ。

アイルランドの旅では、ディングル半島からアラン諸島、かつて女海賊が暮らしていたと言われているクレア島、ドネゴール地方を中心にフィールドワークを続けた。それは遙か先史時代、「古代人は何を思想したか」という問いを胸に抱いていたからだ。結果、僕はヨーロッパの最西端に位置するこの島々で幾千年も前に築かれた円環の城塞は、人類が世界を内部と外部に初めて分け隔てた初期の構造物だったのではないかと思うに至った。つまり、それまでの歴史において、世界は常々外部に属していたのではないだろうか。内的な存在は、人が円環を築くことで初めて抽象的なものではなくなり、内なる思想の素型をも結晶させたのではないだろうか。 (『Storm Last Night』本文より)

The storm passed away as the roaring of the ocean subsided.

Relieved to hear my heart beating, I warmed myself in turf flame.

The rain had already stopped, and the ocean was calming itself.

No one knew the length of time that had passed.

The only memory of the storm was the many whirling patterns left inscribed on the ground.

In my journey to Ireland, my fieldwork was centered in the region from Dingle Peninsula to the Aran Islands, Clare Island known to be the home of a pirate queen, and County Donegal. I was deeply preoccupied by a question about prehistoric times: “What were the ideological issues of the ancients?” Throughout my journey from island to island at the westernmost edge of Europe, I came to believe that these circle forts must have been humankind’s earliest constructions discriminating inner spheres and outer spheres. In other words, until then, people must have lived only in the outer sphere. By constructing a circle, an internal existence became something concrete and not abstract for the first time. The basic concept of inner ideology may have crystallized then. (From the text of Storm Last Night)

今回の旅だが、一見すると南北への旅に映る部分があるのだが、実際にはそうではなく、先に北端へ降り立ったことで、実は南方へ、南方へと目指す旅となっていった。つまり日本の最北端スコトン岬に立った時、全ての日本が自分の南側に位置していることを知り、いつしか日本列島の根を探る旅となっていったということだ。また、最南端の島で聞いた、興味深い話しもここに記しておきたい。島の人々が存在することのない、南波照間島という島の存在を信じてきた歴史があるというのだ。それはやがてニライカナイ(我々の住むこの世界とは別の、もう一つの神々の国。あるいは異境。)の存在を巡る伝説へも発展してゆく。これは、古代から人間が「こちら」と「あちら」を結び留め、信仰を伝承し生き続けてきたことの証なのではないだろうか。

(「果てのレラ」展覧会カタログより)

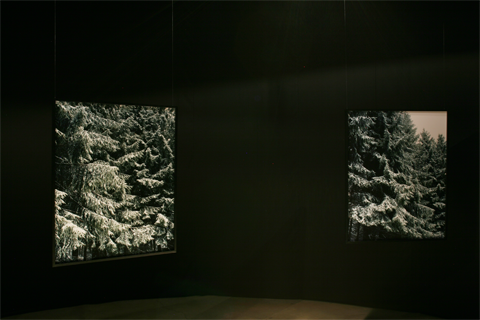

2009年、メルシャン軽井沢美術館で開催されたグループ展「もうひとつの森へ」のため、ドイツ南西部のSchwarzwald(黒い森)と呼ばれる地域で撮影した作品。

陽春の頃、ドイツにあるSchwarzwald(黒い森)を訪れた。早朝、森の始まりを予感させるような小さな樹に光が降り注いでいる。思わず身を縮め、枝を見つめる。樹は人と同じようなところがある。日々、伸びたい思いと広がりたい思いが絡み合い、大きな存在のそばで生き方を教わり育ちたいと願っている。ならば年月を味方につければよい。百年の歳月といまここで約束を結べばよい。

(雑誌『Esquire』 JUL. 2009 Vol.23 No.7より)

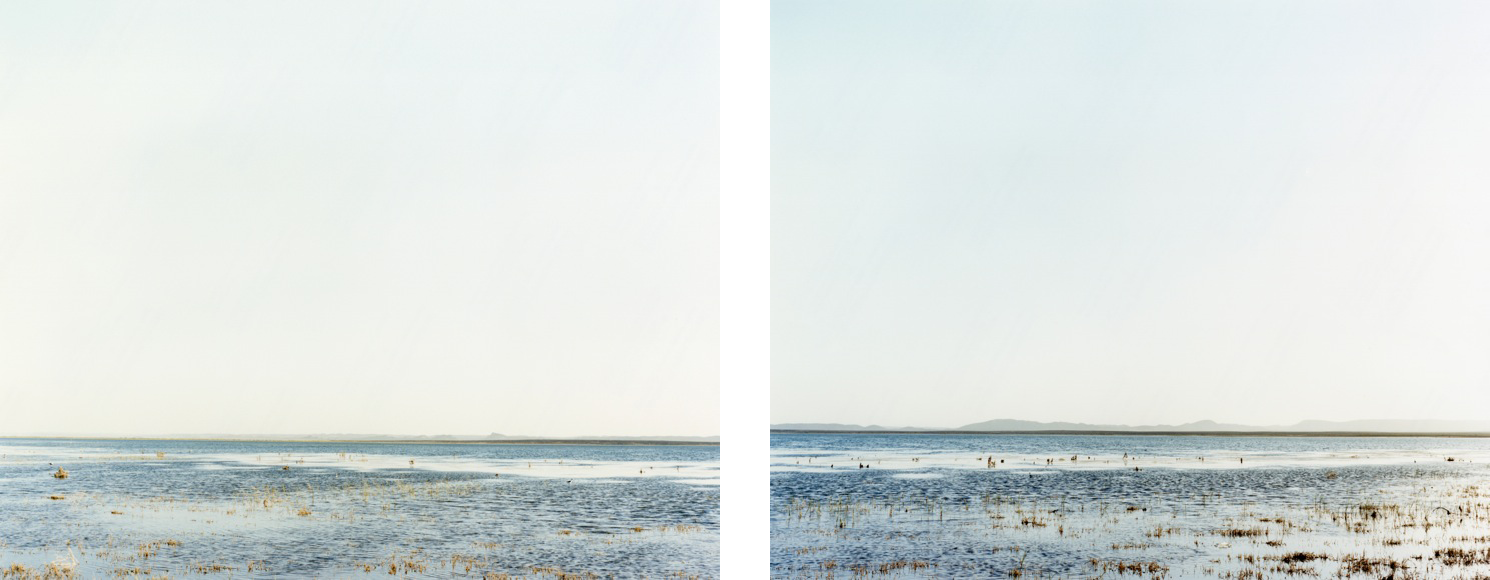

津田が辿り着いた答えは、「風」であった。始まりも終わりもなく、留まることなく「移動」し続ける「風」。「いま」「ここ」も千年前も、そしておそらく千年先も流れているであろう「風」を、世界を繋ぎ保つ存在のひとつと考え、植物のゆらぎなどを介さずに視ることから制作をスタートさせた。

「風」 を知るには「風」と共に生き、「風の民」ともいうべき遊牧民に教えを乞うのが一番だ。津田が風に導かれ辿り着いたのは、遊牧民や少数民族がいまも昔ながらの生活を続けている、中国、モロッコ、モンゴルの3地域。津田はそれぞれの地域に暮らす「風の民」を訪ね、そして共に時を過ごした。

長い旅のなかで撮影した風景は、帰国後現像、印画紙への焼付というプロセスを経てスガタを現す。隔たった3つの地域で、アングルや距離を変えて撮影した風景が、何故か一筋の帯として違和感無く結ばれて、津田の新作は完成した。

(中略)

遊牧民は別の土地に移動するとき、「香」を焚くのだという。彼らが立ち去ったあとに煙が立ち上り、「風」にのって流れていく。自然のダイナミズムに「人」の営みがそっと寄り添って、世界を結び保つ透明な帯が浮かびあがる。

(「SMOKE LINE」資生堂展覧会カタログ、森本美穂テキストより)

The answer Tsuda came up with was “wind.”

“Wind” has no start or finish, it never stops and just continues “moving.” Tsuda thought that wind is “now,” “here,” 1,000 years ago and probably 1,000 years hence it will still be flowing and continue to join the world, so started to produce the work while choosing to overlook its more obvious effects on such things as plant life.

To know “wind” requires living with “wind,” so the best way was to find out from nomads, who probably should be called “people of the wind.” Tsuda was carried by the winds to three areas in China, Morocco and Mongolia where nomads or minority tribes continue now to lead a lifestyle they have maintained since the distant past. Tsuda met the “people of the wind” in each of these regions and spent time with all of them.

Scenes he photographed during his long journey were developed upon returning to Japan and printed on to developing paper to give them a form. Several photographs of scenes taken at different angles from the three different regions were joined together as one in a single belt without creating a sense of being out of place and Tsuda’s new work was complete.

(An omission)

When nomads move to a different area, they are said to burn incense. When they leave a place, the smoke rises in the “wind” and is carried off. When the lives of people are gently inserted into the dynamism of nature, the idea of a world linked by a transparent belt floats to the surface.

(From “SMOKE LINE” exhibition catalog of Shiseido Gallery, text by Miho Morimoto)

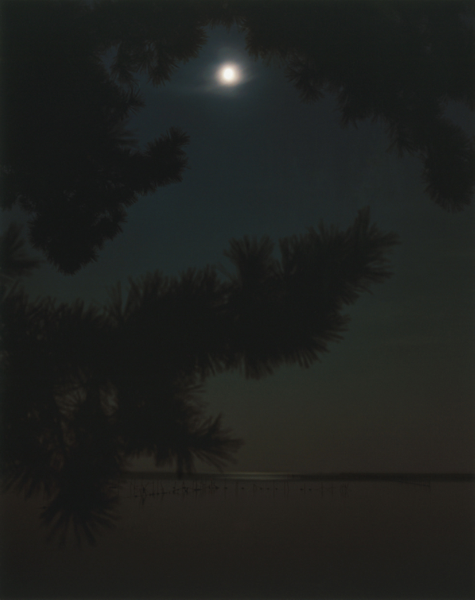

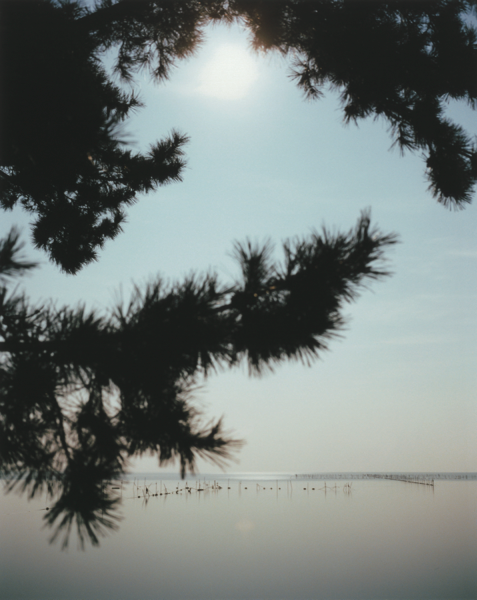

月の径(一)

歴史と共に絶滅していった動物たちが数多くいたように、湖上の風景にもその姿を幾度と変え、生まれては消え去っていった舟たちの姿があった。

「琵琶湖」と呼ばれる内なる海。そこに物語を見た。

今は物語。しかし、時が江戸時代の頃では日常の光景ではなかったか。「淡海録」によると1689年頃、琵琶湖には1348隻もの丸小船が往き来していたという。その浮かぶ姿は時折波の大きな海とはちがい、湖特有の静かなものとなり、見る人は浮世絵図のようにも眺めたという。

時は流れ、2007年の今、湖面にはその面影を持つ舟はもはやただの一隻も見ることがない。

まわりに残されたのは、ごくわずかな資料的な舟の断片と描かれた絵図の中に浮かぶ帆舟の姿である。

この世の中でその役割を終えたものとは不思議なもので、姿を消してからは物語の中へと居場所を移してゆくのが常である。かつてのニホンオオカミのように。

僕は進路をかつての湖上へと向けた。姿を消した舟に乗って。

2007年4月

津田直 (『漕』序文より)

Like many animals which had become extinct along the history, the view on the lake had changed itself many times as well, with boats emerging and disappearing.

The inner sea called “Lake Biwa” is where I found my story.

It has become a tale now. It was, however, perhaps an ordinary scene in the Edo period. According to “Omi-Roku,” the old record about Lake Biwa, 1348 marukobune boats are said to have passed to and fro on the surface of the lake around the year 1689.

The appearance of the boats sailing on the lake, once in a while being quite distinguishable from that on big waves of an ocean, was very calm as was characteristic of the lake boat, and people looked at the scene as though it was a picture from Ukiyoe paintings.

Time has elapsed and now in the year of 2011, not a single boat having resemblances of the past is in sight.

Merely a few fragments of the boat for display purposes and a drawing of the boat sailing are the only remains in the area.

Strangely enough, after completing the assigned lifetime role, works of nature seem to find their ways to exist inside a tale. As with ancient Japanese wolves…

I directed my course towards the ancient lake. Aboard a vanished boat…

April, 2007

TSUDA Nao (From preface of Kogi)

深い霧に覆われた湖や陽光を浴びて屹立する山の岩肌。それらは極めて魅力的な風景であると同時に、複数の映像の間にある時間の隙間を際立たせる。視る者の想像力にとって最も刺激的なのは、実はこの映像の残余としての時間の存在なのだ。それ故に津田は日付けという時間的な指標を作品のタイトルに用いる。そのいっぽうで撮影地の情報は全て匿名化されている。その場所はまだ名付けられていない何処かであり、そこは新たな眼差しによって発見され続ける。「出来事をつかむことは、その定められていない場所にひとつの場所を与えることだと僕は考えている」と津田は語る。それでは私たちがそこに近づくための回路はどこにあるのか。その問いかけへの答えは、おそらく作品そのもののなかに隠されている。 (hiromiyoshii「近づく」展プレスリリース、鈴木布美子テキストより)

Lakes clouded in thick mist, lofty rock face bathed in sunlight. They are extremely stunning sceneries and at the same time highlight the time gaps that lie between multiple images. What is most stimulating for the viewer’s imagination is actually the existence of time as a residue of image. This is why Tsuda uses the date, which is a time indicator, as the title of his works. On the other hand, the information on the location is kept anonymous. These places are yet to be named, and are constantly discovered through a new gaze. “I believe that capturing an incident is to offer a place to a place which is not yet situated”, says Tsuda. So where is the circuit that brings you closer to these places? The answer to this question is perhaps hidden within his works. (From the press release of hiromiyoshii Coming Closer, text by Fumiko Suzuki)