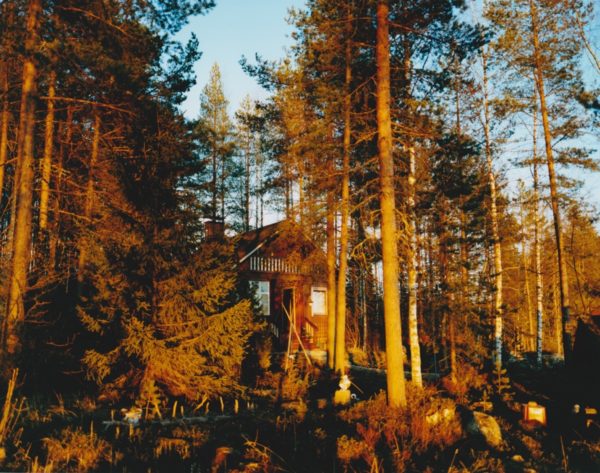

北欧に位置するフィンランドでは、夏の訪れが日本に比べて遅くにやってきます。初夏を迎えた5月、僕は南西部に在るヴァーノ島に滞在していました。フィンランドの沿岸地域にはおよそ40000もの島が在ると言われています。バルト海に面する近くの群島だけでも3000は在り、キミト島の先端にあるカスナスの港からフェリーでヴァーノ島へ向かう途中、僕は島影ばかりを眺めていました。友人に紹介された赤い屋根のコテージに辿り着き、島を歩き始めると、数日前まで固く閉じていたであろう新芽が、開こうとしているのが目に留まりました。眩しい陽光が数日照らし続けたことで、一気に夏がやってきたのです。岩陰から伸びゆく草木。新緑に萌える木の葉は、まだ雛鳥の産毛のように柔らかく、風に揺れていました。普段は人口15人程の小さな島で、空を飛ぶ白鳥の羽音までも聞き取れるくらい静かです。けれど、夏の間は繁殖のために渡り鳥が集まり、羽根を休めるように、フィンランドの人々も休暇を過ごすために島を訪れるので、賑やかな季節がやってきます。この旅で出会った人に島への道を尋ねたところ、彼はヘルシンキから船でやって来たといいます。ここへやってくる人々にとって夏の休暇は、それぞれの船旅と共にあるようです。 (「辺つ方(へつべ)の休息」展@太宰府天満宮 会場テキスト「群島での夏のはじまり」より抜粋)

In Finland, situated in Northern Europe, the arrival of summer is much later than that of Japan. In the early summer month of May, I was staying at Vänö Island, in southwestern corner of Finland. 40,000 islands are said to exist in the coastal area of Finland. Archipelago facing the Baltic Sea is said to number 3,000, and while heading to Vänö Island in a ferry from Kasnäs harbor at the tip of Kemiönsaari, I was constantly following vague outlines of islands in distance. After reaching the red roof cottage recommended by my friend and setting out for a walk, numbers of new buds which were probably not seen until a few days before caught my eye. They were just about to sprout. The bright sun shining for a few days called for the summer all at once. Plants were beginning to grow from rock crevices. Fresh green leaves of trees, appearing to be soft as peach fuzz of baby birds, were swaying in the wind. Its regular population being only 15, the tiny island was so quiet that we were able to hear flapping of wings of swans flying above. But, during the summer months, the island becomes lively with visitors coming on vacations as though migrating birds resting their wings when they gather for breeding purposes. When I asked a traveler whom I met during my stay how he came to the island, he told me that he came from Helsinki by boat. It seems that summer vacation for those who come to the island is always together with each person’s boat trip. (Text from Beginning of Summer in an Archipelago by Nao Tsuda, Tranquility at the Shore exhibition at Dazaifutenmangu)

ここは森の入口。ここから、どう歩くのか、どこへ向かうのかは自由である。小さな森のようにも、深い森のようにも思える。森とは、明確な形のない、往々にしてとらえにくいものなのだ。

津田直もまた、森の入口に立った。5年前、リトアニアを訪れた時のことである。日本から約8000km離れたこの小国は、私たちの多くにとって未知の場所だろう。意外なことに同じヨーロッパでも、リトアニアを遠い存在だと感じる人は少なくない。それは、地理的な要因に加え、近隣大国による侵略が続き、28年前まではロシアの占領下に置かれていたという歴史的背景、そして、遡ればリトアニアがヨーロッパで最後にキリスト教を受け入れた、いわば異端の地であったこととも無関係ではない。この地域には、元々は日本と同様に多神教信仰が根づいており、太陽、星、雷や動植物などの自然を崇拝するアニミズムが浸透していた。

津田は、これまでも異端の地を旅してきた。しかし、それは異端であることが理由だった訳ではなく、「消えゆくものを、写真を通してつなぎ止める」という揺るぎない姿勢を貫くとき、モロッコやモンゴルの山峡、北極圏、ヒマラヤ、ミャンマー、沖縄などの奥地にたどり着いたのは必然だった。津田を呼び寄せた、消えゆく「もの」とは何であろう。それは、「文化」という言葉に近いかもしれないが、一語では到底括りきれるものではない。それは、言語化すればこぼれ落ちてしまう「何か」、決定的瞬間をとらえた1枚だけでは語れない「何か」である。津田はこうした形を持たない「何か」を、口承のように、余白や間(はざま)、象徴を織り交ぜながら記録する。口承に用いられる言語は場所や時代が変われば理解は難しいかもしれないが、写真という視覚言語は時空を超えるだろう。津田の写真は、時と、場所と、私たちがすべて一本の線で結ばれていることを静かに告げている。

ここにある作品は、その森が、遠くの小さな国に、すぐ近くに、古代に、現代にも未だあることを、そして、この先も存在し続ける希望を示す。来た道を戻ってもよい。気に入った場所で佇んでもよい。こうした体験を通して、私たちと森はより強くつながっていくのだから。 (「エリナスの森」展@三菱地所アルティアム 序文 菊田樹子)

Here the entrance to a forest is open. Then it’s your own choice how to walk through it and to which direction to take a step. It might appear to be either a small and deep forest. As general the entity of a forest is something obscure to specify the outline and often hard to figure out.

It was five years ago that Nao Tsuda also arrived at a door to a forest when he visited Lithuania for the first time. For most of Japanese people, such a small country about eight thousands kilometers away from Japan might be a strange place. However, to our surprise, it is parallel even to many people in Europe that Lithuania is regarded as somehow unfamiliar nation state. In addition to the geographical factor, its historical background can bring such a sense of distance from other nations. Following a period of invasion by neighboring powers, it had been under the rule of the former Soviet Union until they won the independence twenty eight years ago. Moreover, considering a long religious context, it matters the fact that Lithuania had been recognized as the land of “paganism” and it was the very last pagan state that adopted the conversion to Christianity among all the European nations. Originally in this region, the ancient religious framework of polytheism had been deeply rooted, which we can find a similarity to that in Japanese and the animism in worship for the nature, including the sun, the moon, stars, the thunder and creatures of both plants and animals had been predominant throughly among their folk.

As a photographer, Nao Tsuda has traveled around various distant lands across the world. Actually his journey was not motivated by the heretical context in the locations, but indeed he constantly pursued his original way based on a firm faith in his mission: “To tie up with something that is going to disappear in the world thorough the art of photography”. As a natural consequence, he found himself inevitably oriented to those hinterlands or the deep interior of characteristic fields such as valley and mountains in Morocco or Mongolia, the Arctic regions, Himalaya, Myanmar and Okinawa Islands etc. What is “something that is going to disappear” that lead him to work for it? One can never define and comprehend it at all in a single term such as “culture” even though it seems to approximately represent it. We have to compromise that “something” is what any trial of verbalization ends up in losing its essence and a piece of fragmental picture that shot a decisive moment can’t describe completely. To record “something” like that which is impossible to deal with any form, Nao Tsuda composes a tapestry, editing symbolic elements with marginal or interval space, as if making an archive of oral history. To hand over memories in the oral tradition, it happens that the language itself would make it difficult to understand depending on conditions of times and locations. On the contrary the visual language of photography is universal to transmit the contents beyond the realm of time and space. Then we can perceive his works of photography silently affirm a status that time and space and our being are all tied together in a line.

This exhibition of a series of works shows us not only the situations that this forest actually exists in a small distant country but also it does just close to ourselves to relate ancient and modern times and further, it manifests a hope of the possibility that it will continue in the future, too. To appreciate the entity of Elnias Forest we can go back our way at any point, or can find some spot to stay and stand still where we want. All those processes are essential to our experiences that enable us to come to connect with the forest more intensively. (Text of Elnias Forest exhibition at Mitsubishi Estate ARTIUM, Preface by Mikiko Kikuta)