写真はフィリピン・ルソン島のピナトゥポ火山周域のものだ。ピナトゥボ火山は、90年代初頭に大噴火したが、その成層圏にまで達するほどの噴煙と灰により、その年、世界中の夕焼けが異様なまでに赤く変化したほどだった。大地は吹飛ばされ火口湖となり、大量の灰が地につもり、土石流を生み、土の河が人も家も森林すべてを洗い流した。まるでノアが体験した洪水のようだ。破壊に見えてしかし、それは、「新しい道」の出現でもあった。その地に住む者(彼らは2万年前からピナトゥボ山麓に住みつき、肌の色が黒いのでネグリートと呼ばれる)は、荒涼たる場所から、新しくくらしを生む。津田はその中のアエタ族の集落で一時を過ごす。その首(おさ)であるローマン・キングととも行動し、さまざまなことを教わることになる。灰の中から最初に芽を出し、実るのは、amukawとよばれるワイルドバナナであった。子どもたちが、磁石を使って河原の水の中から砂鉄をとって売る。ここには、近代文明がつくったものなどは、一切流されて、無い。ある日津田が、ローマン・キングに誘われ山の頂上で見たものは、かなたから来る人々の姿だった。彼らこそ、大噴火後も先祖から受け継ぐピナトゥボの神、アポ・ナマリアーリを信仰するため、再び山のそばへ帰っていった人々だ。 灰混じりの川を数時間かけて歩き集う者たちは、互いの物を交換しあい、くらしに必要な糧を得る。火山の破壊のあとで生まれたもの、景色の中で交わり生まれるもの。小さなワイルドバナナは糧の中心的存在であり、心である。津田は、それを知る。 (「On the Mountain Path」展@Gallery 916 後藤繁雄 「山の目になる 津田直の写真のために」会場テキストより抜粋)

Photographs are of the area around Mount Pinatubo on the island of Luzon in the Philippines. Mount Pinatubo experienced a major eruption in the early 1990s, billowing smoke and ash as far as the stratosphere to the extent that in the year in question sunsets around the world turned unusually red. Earth was thrown into the air and a crater lake was formed, a large quantity of ash accumulated on the ground, and lahars occurred, sweeping away people and houses and forests in rivers of mud. It was almost like the flood that Noah experienced. It looked like complete destruction, but at the same time it represented the appearance of a “new path.” The people living in the affected area (who settled at the foot of Mount Pinatubo more than 20,000 years ago and are referred to as “Negrito” due to their dark skin color) are forging new lives out of this scene of destruction. Amidst this, Tsuda spends time in an Aeta village. He works alongside the village headman, Roman King, and learns various things from him. The first plant to put its head above the ashes and produce fruit was a wild banana known as amukaw. Children use magnets to remove iron sand from the riverbeds, which they then sell. Here, everything produced by modern civilization is gone, washed away by the lahars. One day, Tsuda is led by Roman King to the top of a mountain from where he sees people approaching from the distance. They are people returning to live by Mount Pinatubo, drawn by their faith in the deity of the mountain, Apo Namalyari, a faith that remains strong even after the 1991 eruption. Gathering after walking for hours along rivers clogged with ash, they exchange belongings and acquire enough provisions to make a living. New customs that emerged in the wake of the destruction wreaked by the volcano, changes in the surrounding landscape. The small wild bananas play a central role in providing nourishment, both physically and spiritually. This much Tsuda knows. (From the text Becoming the eyes of the mountains – Looking at Nao Tsuda’s photographs by Shigeo Goto, On the Mountain Path exhibition at Gallery 916)

2013年夏、アーティスト・イン・レジデンスプログラムでスイスのクラン・モンタナにて滞在制作した作品。

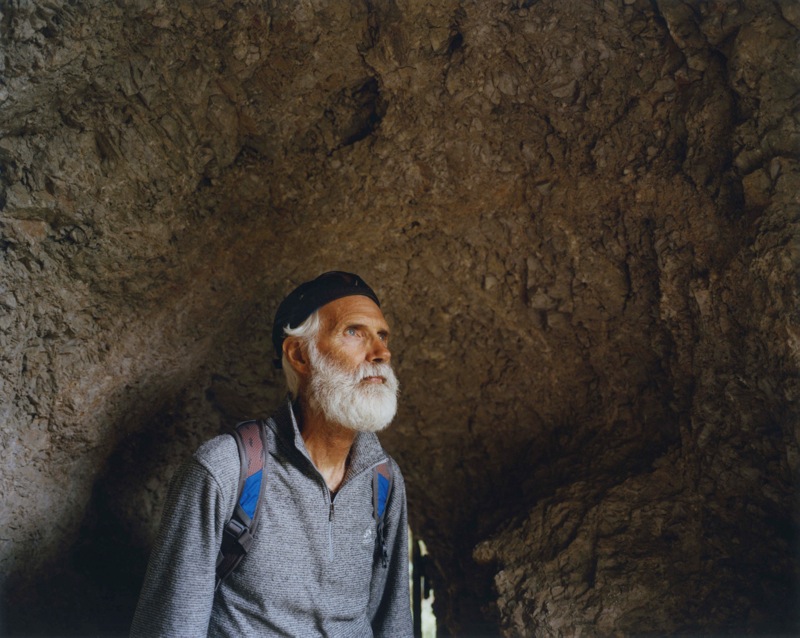

2013年9月に訪れたスイス・ヴァレー地方の滞在制作では、はじめにその土地を歩き回ることからフィールドワークが始まった。僕は標高4000m峰が連なるアルプスの山脈に囲まれた地域で、谷から谷へと渡り歩き過ごした。それはまるで天から降り注いだ雨水が自ら川を築き、山に線を描いてゆくような流れと近いものだった。

その過程でいつしかBisse(ビス)と呼ばれている水路、さらにそこへ寄り添う細い山道と出会い、その魅力に僕は引き込まれていった。Bisseとは氷河から溶け出した水や雪解け水を活用した灌漑用水路の名称で、千年近く前から村人が中心となり建設・管理してきた。かつては、主に牧草地に水を運び動物たちや農地を豊かにするためのものであったようだが、今では葡萄畑に引かれたものなどが一部その姿を留めている。

ヴァレー地方独特である山間部の水路は、途切れ途切れではあるが今でも各所に残されていて、地図から探り出しては繋ぐように歩いて回った。すると足音は水の流れに掻き消され、身体は水に運ばれてゆくような錯覚を起こし、ぐっと山に近づいた気持ちとなっていった。

又、Bisse du Ro やBisse de Vercorinでは伝統的な工法で水路を修復する男達とも出会うことができた。Bisseを流れる水は水源に始まり、山の傾斜を活用した水路を経て、やがては人々の暮らす土地を目指してゆく。だが途中には絶壁もあり、そこでは木で組まれた箱型の水路が水を溢さぬように運んでゆく。 (「Crossing Views I」展覧会カタログ、津田直「NOAH」テキストより)

A series which has made by artist in residence at Crans–Montana in Switzerland on Summer, 2013.

In September 2013, I went to the Valais region of Switzerland to do an artist residency and began my fieldwork by going about on foot. I spent the days walking from one valley to another, surrounded by a continuous range of Alpine peaks soaring to an altitude of 4,000 meters. These journeys, I felt were almost like rivers formed of fallen rain, etching lines in the mountains.

At one point during my preambulations, I came across and became enchanted by ancient water channels and the narrow mountain trails that led to them. Fed by snowmelt or glacial runoff, these channels, called “bisse” in French, have been built and maintained for almost a thousand years largely by villagers as a source of irrigation water. Thanks to the bisses, which were constructed mainly to water the pastures, livestock and farmland flourished. Only some of these channels, like those used to irrigate vineyards, still exist in their former condition.

The bisses are a distinctive feature of the mountainous areas within Valais, and though largely discontinuous, can still be found in various places. I located them on the map and visited each one on foot, as if I were connecting them. During my approach, the sound of my footsteps would be drowned out by the sound of water, giving rise to the illusion of being carried by the flow, of being closer to the mountains.

Following the Bisse du Ro and Bisse de Vercorin, I encountered men who use traditional techniques to repair and maintain these water channels. Starting from their source, the bisses carry water down the mountain slopes to locations inhabited by people. To prevent the water from falling off the face of cliffs along the way, box-shaped channels made of wood were constructed to carry the flow. (From Crossing Views I exhibition catalog, “NOAH” text by Nao Tsuda)